Ashraf Jamal, writer and cultural theorist, reviewed the Wild Wild Life exhibition for South Africa’s leading contemporary visual arts publication: Artthrob.

Wild Wild Life is a group exhibition, curated by Alex Hamilton and on show online in the Gallery @ Glen Carlou until the 26th of July.

The review can also be read on artthrob.co.za

Wild Wild Life at Glen Carlou – A review by Ashraf Jamal

It is hard to write about every work in a group show, one generally, vaguely, hopes something sticks. One – whoever that ‘one’ might be – attaches his-her-their focus to what they think matters to them. As our tangerine monster would say – SAD – but it’s what we do, we fixate. Mostly we look about us through a glazed veneer. Our eyes aren’t wired to look at anything anymore, distracted as we are by distraction itself.

Seeing things through a looking glass – online – only compounds the futility. Lockdown, and business, dictates one examine art while deprived of direct access. Then again, access is never ‘direct’, even when physically face to face with an artwork. The sense we make is our own, well, what we claim as such. First in line, at nine, to see Courbet’s vagina at the D’Orsay – because I wanted to be alone in the room, the first to clap my eyes to the ‘Origin of the World’ – doesn’t mean that a private view of another’s privates amounts to direct unsullied access. Everything we feel-want-think is wired to some server somewhere.

Tracy Payne, Fluorescence, 2013. Pencil crayon, spray paint, chalk pastel, charcoal, Japanese ink, liquid acrylic and tulle on canson montval 300g paper, 110 x76 cm

‘Wild Wild Life’. If the title is not risqué enough – a nod to Lou Reed – the subtitle – ‘The debauchery of man’ – makes a case for the presumption that: 1. Life has lost its sure footing, 2. It is debauched. Courbet would surely rub his sex-addled hands in gleeful anticipation. But sex is not the focus of Alex Hamilton’s curatorial project, though the website does place Tracy Payne’s painting of a women on shocking pink tiptoes glaringly in view. At the top-end, beneath a sliver of beige toile is a black vaginal V, more void than substance, flanked on the inner and outer margins of the strained legs by a further extension of that void.

Chiaroscuro is a Renaissance concoction, a way to cut out and hotwire the way we look at the world. It is tough, stark, declamatory – it hits you in the face. Payne does this extremely well. You can’t but look. It’s not the vagina, not quite the legs, it’s the shocking pink hose that hooks, the way it bounces off and seers the skin, runs electrically along the sheer length of a perfectly turned pair of legs. Debauched? Wild? Or simply irresistibly alive? Mistaken as Pop Art – certainly its hither velvet underground – Payne’s paintings owe far more to Caravaggio. She is a fix of sorts, somewhere between that murderous thug and Marlene Dumas.

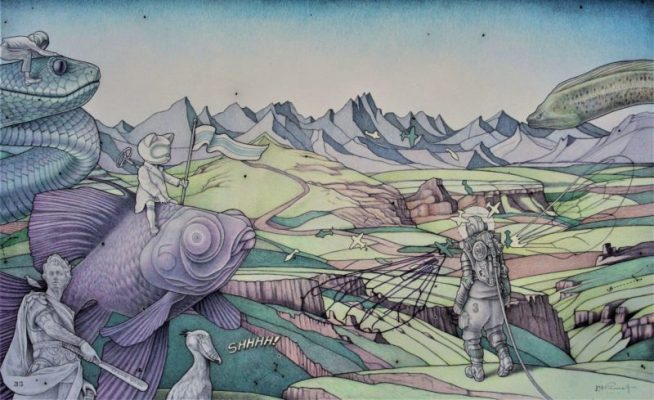

Æiden Swan, Talking to Fish I. Ink, tempera and charcoal on paper, 71 x 50cm

Æiden Swan, Talking to Fish I. Ink, tempera and charcoal on paper, 71 x 50cm

Shocking pink is browned into stale blood in Æiden Swan’s similarly tensed depiction of wild dogs (coyotes?) and fish (bream?), and a white bird (vulture?) thrown in the mix. I’m in a spin-cycle, the wild dogs’ fur all soggy. In Milwaukee, where I embarked on a PhD by mistake, I was once told of a cat and a horse caught in a tornado somewhere in the American Midwest. They were airlifted and thrown into the neighbouring state. The horse, on steroids, too muscly for its own good, died on impact. The cat, sleekly armed with nine lives, maybe more, rolled into a ball then snapped back up before making its way back home to a lifetime of crème fraîche. In Swan’s work we’re in the tornado, and there’s no way out. The spin-cycle is stuck on a Nietszchean repeat – a hell of the eternal return. I must say, I feel for the fish. No one’s defying gravity, or swimming upstream. Except for that damned bird, zenned out, its talons firmly hooked into lumpy neck fur.

Another bird, claiming to be fragile, or just hooked to a sign that states itself to be, pops up in Ella Cronje’s installation. Words are never what we take them to be, and neither, it seems, is this gloopy looking bird. Then more dogs, caught in a snarling rumble in a work by Frans Mulder, as etched, as edgy as Payne’s electrocuted legs. Dogs in a fight aren’t funny. I raced mine to the vet, blood leaping from its jowl, when some rabid nutter broke from its leash because IT – that indefinite unnameable nightmare – wanted a piece of my pooch. Whose name is Mica, by the way. But I digress. What hits you in Mulder’s work is meanness. It’s in the body language, in the artist’s line, in the smudged sooty fuckery of it all.

Frans Mulder, Wild Dog Man. Pastel on fabriano watercolour paper, 150cm x 120cm

Frans Mulder, Wild Dog Man. Pastel on fabriano watercolour paper, 150cm x 120cm

But maybe I’m wrong. There is also something weirdly tender, weirdly human, about the paws of the one dog and the way they softly press upon the other. Ominous, yet not? Hm…. In the back of my head, or wherever thoughts bob about, I’m reminded of Alexander’s Butcher Boys, our maleficents, our forever chemicals, our nightmare from which we are never likely to waken.

Skulls and bones. Conrad Botes. Hannalie Taute. Marinda Combrinck. And more dogs, or bears, as humans – Stephen Rosin. But let’s stick with bones. ‘Their faces are distorted as the skin has started to melt and decay … In places their spines have broken through the flesh; you can see the plates of their skulls. They have grown horns’ – Mike Nicol, the crime writer, describing the Butcher Boys. ‘Vengeance had driven them mad’. Is there something similarly ominous at work in this airing of ‘Wild Wild Life’? 2020 and we’re still in a State of Emergency? Have we never quit our murderous ways? Are we just sick puppies? Or sad bears? Or brawling dogs? Or fluffy-fat-weird-catty-dogs caught in a permanent spin-cycle?

Botes is Death’s broker. His Red Right Hand. Combrinck, with her forensic eye sees the living and the dead. Another spin-cycle. Taute, like the weavers of old, stitches death, like a gap, into her tapestry of flowers, a giant bug and, yes, another smug bird, very Toucan-y and flightless to me. Here life and death go on their merry dance. Here the void creeps in, just so, to munch up all that fecund delight.

Conrad Botes,Untitled Landscape. Oil on canvas, 200 x 80cm

Conrad Botes,Untitled Landscape. Oil on canvas, 200 x 80cm

Collen Maswanganyi suggests that if we are to stick with the golem-like bee and twee butterflies, we’ll need a punching bag. Well, however we square life and death and vengeance and bloodlust and lust, no one, in the squaring, is immune. We might place our goggle-eyed sentries on alert – I’m thinking of Marinda Du Toit’s sculptures here – we might believe we can fend off threat, especially the threat that lurks inside of us – cruel miserable fugly South Africans that we are. Or we might just turn askance, like Thina Dube’s gauzy cheeked red-hatted figure. But the line has been drawn, the blood runs down that face. It quivers through Mulder’s wild dogs. It runs up and down Payne’s irresistibly taut and tremulous legs.

But thank God – kinduv– there’s Peter van Straten’s roast … duck? Oh fuck! It’s a baby! I’m tired. Trying to ‘see’ shit but can’t. Sunlight pours in to illuminate the cook’s yellow rump. Everything, including the weird looking bird-slash-baby – is aglow. Baby notwithstanding, are we not in some chintzy weirdly glowing Vermeer? Or am I being perverse, ‘denialist’ – terrible word. Baby notwithstanding – are we not also – kinduv – inside Matthew Arnold’s realm of sweetness and light? Or – notwithstanding the ‘baby’ – am I just starved for something wholesome?

Peter van Straten, Cooking the Next Generation. Oil on canvas, 120cm x 90cm

Peter van Straten, Cooking the Next Generation. Oil on canvas, 120cm x 90cm

Fat chance in South Africa. It is, as they say, a Wild Wild Life. Debauchery, butchery, and the numbness that comes with supping from the skull of night sticks. All we can do is lick the grease. I’m thinking of a golden roast, but I don’t eat meat. I’m thinking of shocking pink legs, but I don’t do sex. I’m thinking of coyotes and fish and jackals and bears. Of butterflies and bones and a dark hand spread menacingly, erotically, against a steamed pane … and realise I should stop right here, right now, and put my own filth in a spin-cycle.